Now that it’s warm enough to sleep with the window open, I love waking to the spotted towhee singing before dawn.

Before leaving bed, I listen to the birdsong and try to remember any dreams. I also like to imagine what’s happening in one of my favorite places — a stretch of the Rio Grande in Albuquerque.

It’s a place I visit a few times a week, and I know where there are coyotes and great horned owls, badger burrows and porcupines, and where beavers are denning and building dams. I know which birds have migrated into the valley; where to listen for Lucy’s warblers or watch cormorants. I’ve seen bobcat prints, wondered how far down the valley mountain lions roam, and once, caught a glimpse of a javelina. I love this place, deeply, and I think about it all the time.

Right now, I’m worried.

If you live in the Middle Rio Grande Valley, you’ll have noticed that the river is dropping. Fast.

Long sandbars are emerging in the Albuquerque stretch as the river shrinks, and already, flows are only 86 cubic feet per second in Bernardo. For perspective: On this day in 1985, the river there ran at 5,110 cfs. And over the last 42 years, the median flow on this day was 796 cfs.

Upstream, in Albuquerque, the Rio Grande is running at 300 cfs. (Over the last 52 years, the median daily flow was 1,340 cfs.)

Already, irrigation supplies are constrained, and as I’ve already written this spring, there isn’t much water stored in upstream reservoirs. That also means there isn’t water in upstream reservoirs for the river itself — and the creatures who rely on the waters.

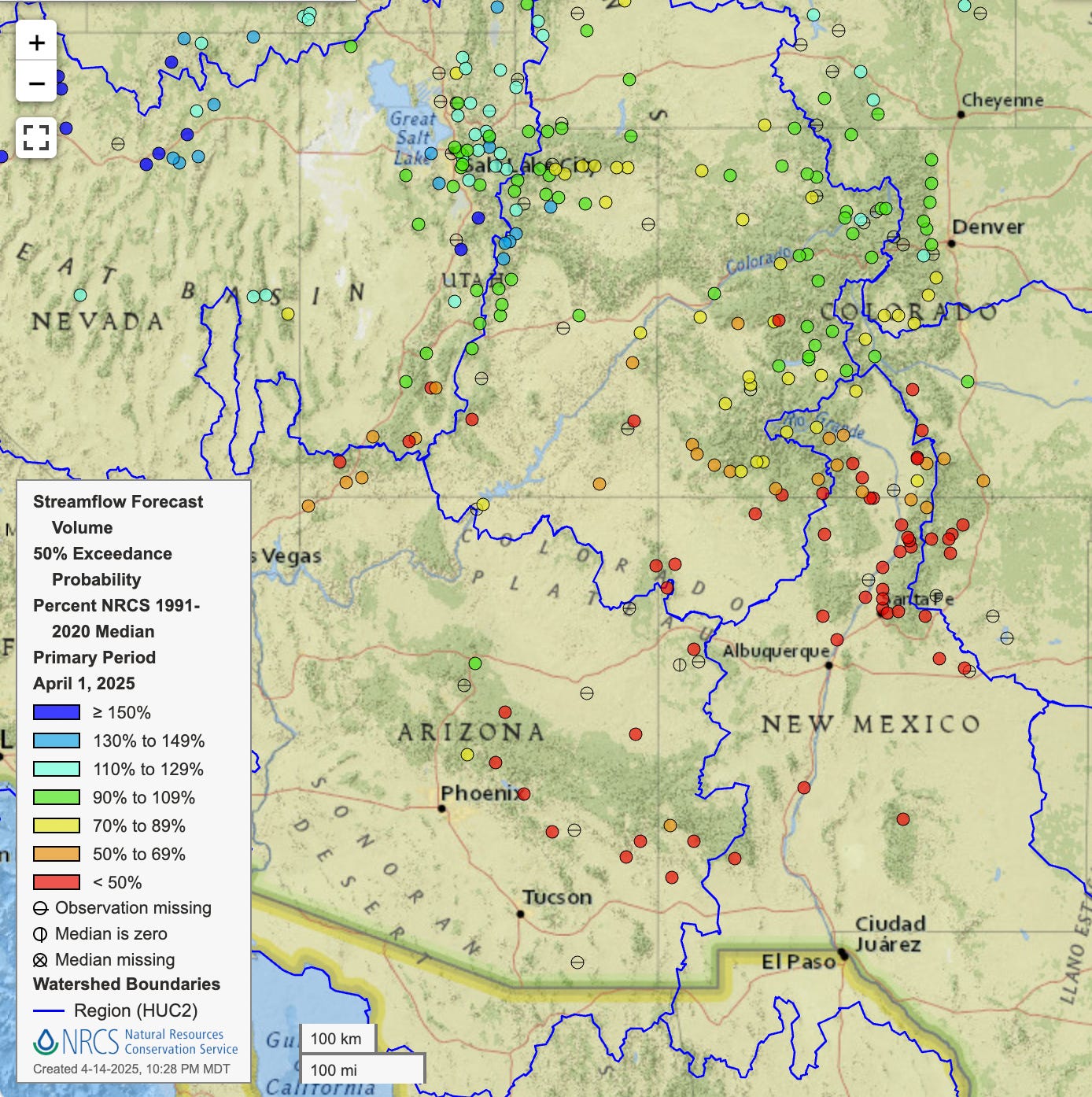

To understand more about what’s happening, you can look at all the USGS stream gauges and read the Natural Resources Conservation Service’s April 1 New Mexico Water Supply Outlook Report.

Here are a few key points from the report:

Basin-wide snow water equivalent (SWE) values in the Rio Grande Headwaters and the San Juan Basin are at 56 percent of normal.

Other basins in New Mexico range from 0 to 29 percent of normal, with “no-snow” conditions in the Gila-San Francisco watershed.

12 sites in New Mexico had record-low snow water equivalent; three more locations were at their second lowest in recorded history. (Here’s a map to look at these locations.)

The spring runoff season has “essentially ended” in New Mexico’s southern and eastern basins, and in northern basins “melt-out began days to weeks earlier than normal.”

You can explore the interactive NRCS map online.

Saturday evening, I sat on the edge of the river, watching wood ducks and cormorants, a pair of herons, and mallards. Right now, the Canada geese are busy guarding nests, and swallows are trying to find enough bugs to eat. Walking back to my car, I passed beneath two great horned owls, saw my first bat of the season, and heard coyotes.

Our water challenges in New Mexico aren’t abstract. And we can’t keep waiting for a better snowpack or a good monsoon season.

As the Rio Grande keeps dropping — and inevitably dries this year — all those creatures and their habitats are at risk. And as our water challenges deepen and grow, I hope we won’t forget that our more-than-human neighbors need us to care for their futures, too.

In the news:

The battle against federal ownership of New Mexico’s public lands (Molly Montgomery, Searchlight New Mexico)

Officials, residents plan next moves to protect Upper Pecos watershed (Danielle Prokop, Source NM)

Why Trump’s executive order targeting state climate laws is probably illegal (Lois Parshley, Grist)

Upcoming events:

Lastly, thanks to everyone who came out to our event last week for Water Bodies: Love Letters to the Most Abundant Substance on Earth.

I really appreciate the support of Dr. Becky Bixby at the University of New Mexico’s Water Resources Program, which sponsored the event, and all the co-sponsors, including the Department of Geography and Environmental Studies, Intermountain West Transformation Network, South Central Climate Adaptation Science Center, Sustainability Studies Program, and the Accelerating Resilient Innovations in Drylands Institute.

Most of all, I appreciated the audience’s willingness to join me in naming their favorite water bodies. I’m still thinking about all the answers, and the collective power of naming and protecting our beloved waters. ❤️

Thanks for including wildlife in assessing the effects of dewatering natural water resources. Decisions here in Cambria prefer to overlook those without a voice in meeting water needs.